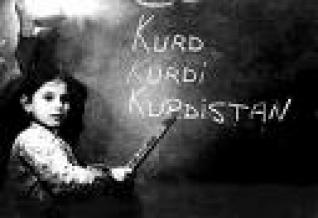

''ΕΚΤΟΥΡΚΙΣΜΟΣ''(''TURKIFICATION''):Turkish state in systematic destruction of the Kurdish language and culture ...

A day in the life of six teachers, 265 students in Turkey

The classrooms at the elementary school in the small, poor village of Böğürtlen are filled to the brim, with just six teachers for 265 students. Complicating their task is the fact that the majority of the pupils, even the smartest ones, start school not understanding a word their teachers say.

The combination of Turkish-speaking teachers and Kurdish-speaking students is not uncommon in Southeast Turkey, which, along with the rest of the country, is celebrating Teacher’s Day on Wednesday. Both languages echo through the Böğürtlen Village Elementary School, a small building amid flat-roofed, gray stone houses in a village of 2,000 people set among brown and yellow fields 125 kilometers outside of Şanlıurfa.

The 265 Kurdish children being educated in combined classes are learning reading and writing in Turkish. Only 100 of the students speak Turkish.

The school consists of three small classes, one of which is a nursery class, each located in a different building. Fifty first-grade students have their lessons in a prefabricated building; some wear blue school uniforms, others lack them. Some have socks with holes, or wear slippers instead of shoes. The classroom building sits on a rough patch of concrete, from which dust clouds arise here and there. The open door allows the odor of dried dung to permeate the room. Trying to control her class, teacher Elçin Löker speaks loudly, saying, “Hush up and sit down.” She neatly spells words on the chalkboard. Though she is speaking Turkish, the answers to her questions keep coming back in Kurdish.

Questions and answers

Teacher Löker turns to her students. “Don’t talk among yourselves,” she says, using a type of sign language along with her words in hopes of being better understood. “Don’t talk,” she says, but the students smile and mimic her in the wrong way, as though she had said, “Repeat after me.” Teacher Löker keeps asking, “All right?” The students all repeat after her: “All right.” But what is all right?

When a girl hurriedly leaves the classroom, the teacher asks, “Where are you going?” She repeats her question five times, but receives only the silent gaze in the student’s shy eyes.

Teacher Löker sometimes asks her students who know Turkish to help her communicate, or tries to utter a few Kurdish words herself. She draws a house on the board and asks, “Is this a house?” The children all say, “Yes.” Then she asks, “Is this not a house?” The class answers “Yes” again.

Some teachers believe pre-school education could be a solution to the language barrier. The nursery class was opened this year to help meet that need.

A graduate of Samsun 19 Mayıs University Faculty of Education, Teacher Löker is from Ankara. She has been teaching in the town of Siverek for two and a half years. This is her first teaching placement. Her husband is a teacher working in Ankara.

Lessons on a rug

The 78 students in the second and third grades are taught in the only classroom in the main building. Technically, there are 93 students enrolled, but some go to work instead of school. The students are packed into the class like sardines in a can. Four or five students share one desk, while a sixth stands nearby with no chair to sit on. A few pupils sit on a rug neatly spread on the concrete floor, leaning forward to write in their notebooks on the ground. The teacher cannot walk around the room lest he step on one of the students.

A few books sit on a few shelves in the corner. Several artworks made by students out of dried beans hang on the bulletin board. These students seem more assertive because they have overcome the language barrier that the first graders face. But it is still difficult for them to express themselves in Turkish.

Teacher Ayhan Pala has been in Böğürtlen village for three years. “I came here knowing about the conditions. Our main goal is to teach perfect Turkish in five years,” he said. “Education is a triangle of student-teacher-family. But families are not involved in school here. Students suffer from a lack of communication in Turkish. So you feel inadequate.”

Teacher Pala said he could ask to be reappointed to another part of the country in August, but that he had not yet decided whether to do so. “I want to help these kids. Any place is a place of duty for us. We belong everywhere,” he said.

A graduate of Samsun 19 Mayıs University Faculty of Education, Teacher Pala is from the Black Sea province of Samsun. Böğürtlen is his first placement as a teacher and he has been there for three years. The child of a middle-class family, Teacher Pala has a sister who attends university. Both he and Teacher Löker were classmates of teacher Emre Aydın in the documentary film “İki Dil Bir Bavul” (On the Way to School), which follows Aydın’s efforts to teach Kurdish children in the Southeast.

Dried dung and computers

The language barrier at Böğürtlen Village Elementary School is compounded by the crowded classrooms, said Teacher Löker. “Since the children don’t understand our language, they feel disturbed. I try to put myself in their shoes. Someone comes to you and tells you something in a different language. This is very difficult,” she said.

“The school lacks so many things. In winter there is a stove for heating. Students are walking in with dried dung on their shoes. The prefabricated classroom fills with either water or mud. If they wear slippers, they cannot get to class,” Teacher Löker said. “Considering conditions both in the village and at the school, anything we do is helpful.”

The school has seven computers, all of them in storage, but frequent power outages would render them useless anyway, the teacher said. “It is impossible to make all students computer-literate. We face difficulty teaching them even ordinary things. So teaching computer-literacy here is like a dream for now,” Teacher Löker said. “We teach them writing and reading in Turkish and try to teach them some manners. We teach the basics.”

Eight teachers in four years

Teacher Mehmet Baştuğ, a native of the Mediterranean city of Mersin, is 26 years old. This is his fourth year in Böğürtlen. Eight teachers have left in four years, he said. But Teacher Baştuğ has stayed. “My conscience won’t let me go,” he said. “I am here until I get married.” Teacher Baştuğ lives in a small house with no water and, frequently, no electricity. He uses plastic barrels and hoses to carry water inside the house, which is next to the school building.

During his first year, Teacher Baştuğ said, he couldn’t sleep due to worrying about how to communicate with his students. So he learned a little bit of Kurdish, barely enough to talk to their families. One of the problems facing students in the area is the lack of a place to continue their education in the village. “We need a secondary school building for the sixth, seventh and eighth graders. If there is such a school in the village, families will send their kids to school,” Teacher Baştuğ said.

A graduate of the Hatay Mustafa Kemal University Faculty of Education, Teacher Baştuğ comes from a family of eight children. His family lives in the Central Anatolian city of Karaman.

‘It is difficult: Turkish at school, Kurdish at home’

Asked, “Which language do you speak at home?” all the students in Böğürtlen say, “Kurdish.” Asked about their father’s profession, they reply, “He sells goods in Istanbul.”

Second grader İdris Karakaş did not speak Turkish at all before he started school. “It was difficult for me,” he said. “Our teachers taught us Turkish. I speak Kurdish at home because my parents don’t know Turkish.”

Third grader Selman Boğa said he learned a little Turkish from his big brother before starting school. “My Turkish is not so good. But if I work hard, it’ll be OK. I want to be a teacher because they speak Turkish very well,” he said.

Fourth grader Zeytin Kengil is one of the students fluent in Turkish. Her family speaks Kurdish at home. “Turkish at school and Kurdish at home... It is difficult,” she said.

Speaking with the first graders without a Kurdish translator is really tricky. Asked how many siblings she has, Şükran Kasuf said: “The first one is Seher, and then Pınar, then Songül. There is Ceylan and Nebat, too.” Asked “How many?” once again, she does not answer.

“Perihan, which grade are you in?” The response is empty eyes. Upon hearing the question repeated, she raises her hand and draws “one” in the air. “What does your father do?” She answers, “My father’s name is Mehmet Özdemir.” Her friend translates the question into Kurdish. This time, Perihan comes back with the right answer: “My father is selling goods in Istanbul.” But her response to the question “How many brothers and sisters do you have?” is a long pause. Just like in the classroom.

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

UMAY AKTAŞ SALMAN

ŞANLIURFA – Radikal

ΠΗΓΗ:

''Hurriyet daily news'' 2010-11-23

.

(O τίτλος,οι''υπογραμμίσεις'' -χρώμα,μέγεθος γραμματοσειράς κλπ- και οι εικονογραφήσεις στις αναρτήσεις γίνονται με ευθύνη του blogger)

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

UMAY AKTAŞ SALMAN

ŞANLIURFA – Radikal

ΠΗΓΗ:

''Hurriyet daily news'' 2010-11-23

.

(O τίτλος,οι''υπογραμμίσεις'' -χρώμα,μέγεθος γραμματοσειράς κλπ- και οι εικονογραφήσεις στις αναρτήσεις γίνονται με ευθύνη του blogger)