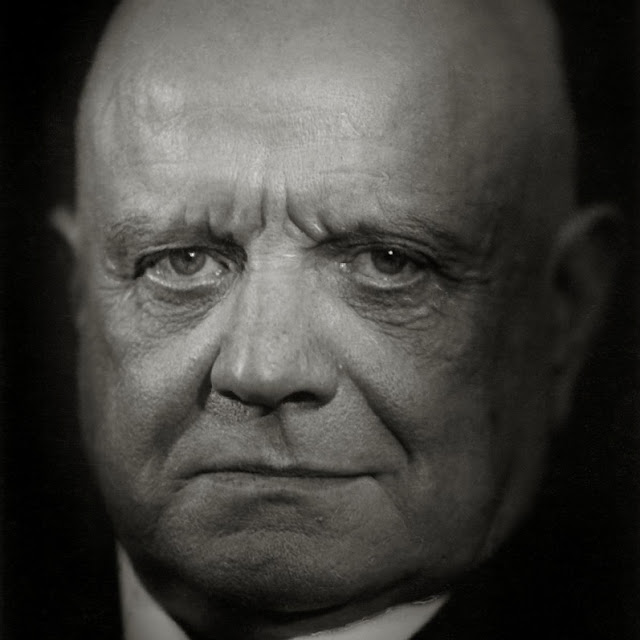

Jean Sibelius.

Finland's Jean Sibelius is perhaps the most important composer associated with nationalism in music and one of the most influential in the development of the symphony and symphonic poem. Sibelius was born in southern Finland, the second of three children. His physician father left the family bankrupt, owing to his financial extravagance, a trait that, along with heavy drinking, he would pass on to Jean. Jean showed talent on the violin and at age nine composed his first work for it, Rain Drops. In 1885 Sibelius entered the University of Helsinki to study law, but after only a year found himself drawn back to music. He took up composition studies with Martin Wegelius and violin with Mitrofan Wasiliev, then Hermann Csillag. During this time he also became a close friend of Busoni. Though Sibelius auditioned for the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, he would come to realize he was not suited to a career as a violinist.

In 1889 Sibelius traveled to Berlin to study counterpoint with Albert Becker, where he also was exposed to new music, particularly that of Richard Strauss. In Vienna he studied with Karl Goldmark and then Robert Fuchs, the latter said to be his most effective teacher. Now Sibelius began pondering the composition of the Kullervo Symphony, based on the Kalevala legends. Sibelius returned to Finland, taught music, and in June 1892, married Aino Järnefelt, daughter of General Alexander Järnefelt, head of one of the most influential families in Finland. The premiere of Kullervo in April 1893 created a veritable sensation, Sibelius thereafter being looked upon as the foremost Finnish composer. The Lemminkäinen suite, begun in 1895 and premiered on April 13, 1896, has come to be regarded as the most important music by Sibelius up to that time.

In 1897 the Finnish Senate voted to pay Sibelius a short-term pension, which some years later became a lifetime conferral. The honor was in lieu of his loss of an important professorship in composition at the music school, the position going to Robert Kajanus. The year 1899 saw the premiere of Sibelius' First Symphony, which was a tremendous success, to be sure, but not quite of the magnitude of that of Finlandia (1899; rev. 1900).

In the next decade Sibelius would become an international figure in the concert world. Kajanus introduced several of the composer's works abroad; Sibelius himself was invited to Heidelberg and Berlin to conduct his music. In March 1901, the Second Symphony was received as a statement of independence for Finland, although Sibelius always discouraged attaching programmatic ideas to his music. His only concerto, for violin, came in 1903. The next year Sibelius built a villa outside of Helsinki, named "Ainola" after his wife, where he would live for his remaining 53 years. After a 1908 operation to remove a throat tumor, Sibelius was implored to abstain from alcohol and tobacco, a sanction he followed until 1915. It is generally believed that the darkening of mood in his music during these years owes something to the health crisis.

Sibelius made frequent trips to England, having visited first in 1905 at the urging of Granville Bantock. In 1914 he traveled to Norfolk, CT, where he conducted his newest work The Oceanides. Sibelius spent the war years in Finland working on his Fifth Symphony. Sibelius traveled to England for the last time in 1921. Three years later he completed his Seventh Symphony, and his last work was the incidental music for The Tempest (1925). For his last 30 years Sibelius lived a mostly quiet life, working only on revisions and being generally regarded as the greatest living composer of symphonies. In 1955 his 90th birthday was widely celebrated throughout the world with many performances of his music. Sibelius died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1957.

(Artist Biography by Robert Cummings)

1. Johan Julius Christian Sibelius.

Jean Sibelius (/sɪˈbeɪliəs/;[1]  Swedish pronunciation (help·info)), born Johan Julius Christian Sibelius[2] (8 December 1865 – 20 September 1957), was a Finnish composer and violinist of the late Romantic and early-modern periods. He is widely recognized as his country's greatest composer and, through his music, is often credited with having helped Finland to develop a national identity during its struggle for independence from Russia.

Swedish pronunciation (help·info)), born Johan Julius Christian Sibelius[2] (8 December 1865 – 20 September 1957), was a Finnish composer and violinist of the late Romantic and early-modern periods. He is widely recognized as his country's greatest composer and, through his music, is often credited with having helped Finland to develop a national identity during its struggle for independence from Russia.

The core of his oeuvre is his set of seven symphonies, which, like his other major works, are regularly performed and recorded in his home country and internationally. His other best-known compositions are Finlandia, the Karelia Suite, Valse triste, the Violin Concerto, the choral symphony Kullervo, and The Swan of Tuonela (from the Lemminkäinen Suite). Other works include pieces inspired by nature, Nordic mythology, and the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, over a hundred songs for voice and piano, incidental music for numerous plays, the opera Jungfrun i tornet (The Maiden in the Tower), chamber music, piano music, Masonic ritual music,[3] and 21 publications of choral music.

Sibelius composed prolifically until the mid-1920s, but after completing his Seventh Symphony (1924), the incidental music for The Tempest (1926) and the tone poem Tapiola (1926), he stopped producing major works in his last thirty years, a stunning and perplexing decline commonly referred to as "The Silence of Järvenpää", the location of his home. Although he is reputed to have stopped composing, he attempted to continue writing, including abortive efforts on an eighth symphony. In later life, he wrote Masonic music and re-edited some earlier works while retaining an active but not always favourable interest in new developments in music.

The Finnish 100 mark note featured his image until 2002, when the euro was adopted.[4] Since 2011, Finland has celebrated a Flag Day on 8 December, the composer's birthday, also known as the "Day of Finnish Music".[5] In 2015, the 150th anniversary of the composer's birth, a number of special concerts and events were held, especially in the city of Helsinki.[6]

Εarly years

Sibelius was born on 8 December 1865 in Hämeenlinna in the Grand Duchy of Finland, an autonomous part of the Russian Empire. He was the son of the Swedish-speaking medical doctor Christian Gustaf Sibelius and Maria Charlotta Sibelius née Borg. The family name stems from the Sibbe estate in Eastern Uusimaa, which his paternal great-grandfather owned.[7] Sibelius's father died of typhoid in July 1868, leaving substantial debts. As a result, his mother—who was again pregnant—had to sell their property and move the family into the home of Katarina Borg, her widowed mother, who also lived in Hämeenlinna.[8] Sibelius was therefore brought up in a decidedly female environment, the only male influence coming from his uncle, Pehr Ferdinand Sibelius, who was interested in music, especially the violin. It was he who gave the boy a violin when he was ten years old and later encouraged him to maintain his interest in composition.[9][10] For Sibelius, Uncle Pehr not only took the place of a father but acted as a musical adviser.[11]

From an early age, Sibelius showed a strong interest in nature, frequently walking around the countryside when the family moved to Loviisa on the coast for the summer months. In his own words: "For me, Loviisa represented sun and happiness. Hämeenlinna was where I went to school; Loviisa was freedom." It was in Hämeenlinna, when he was seven, that his aunt Julia was brought in to give him piano lessons on the family's upright instrument, rapping him on the knuckles whenever he played a wrong note. He progressed by improvising on his own, but still learned to read music.[12] He later turned to the violin, which he preferred. He participated in trios with his elder sister Linda on piano, and his younger brother Christian on the cello. (Christian Sibelius was to become an eminent psychiatrist, still remembered for his contributions to modern psychiatry in Finland.)[13] Furthermore, Sibelius often played in quartets with neighboring families, adding to his experience in chamber music. Fragments survive of his early compositions of the period, a trio, a piano quartet and a Suite in D Minor for violin and piano.[14] Around 1881, he recorded on paper his short pizzicato piece Vattendroppar(Water Drops) for violin and cello, although it might just have been a musical exercise.[11][15] The first reference he to himself composing is in a letter from August 1883 in which he writes that he composed a trio and was working on another: "They are rather poor, but it is nice to have something to do on rainy days."[16] In 1881, he started to take violin lessons from the local bandmaster, Gustaf Levander, immediately developing a particularly strong interest in the instrument.[17] Setting his heart on a career as a great violin virtuoso, he soon succeeded in becoming quite an accomplished player, performing David's Concerto in E minor in 1886 and, the following year, the last two movements of Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in Helsinki. Despite such success as an instrumentalist, he ultimately chose to become a composer.[18][19]

Although his mother tongue was Swedish, in 1874 Sibelius attended Lucina Hagman's Finnish-speaking preparatory school. In 1876, he was then able to continue his education at the Finnish-language Hämeenlinna Normal Lyceum where he was a rather absent-minded pupil, although he did quite well in mathematics and botany.[16]Despite having to repeat a year, he passed the school's final examination in 1885, which allowed him to enter a university.[20] As a boy he was known as Janne, a colloquial form of Johan. However, during his student years, he adopted the French form Jean, inspired by the business card of his deceased seafaring uncle. Thereafter he became known as Jean Sibelius.[21]

Studies and early career

After graduating from high school in 1885, Sibelius began to study law at the Imperial Alexander University in Finland but, showing far more interest in music, soon moved to the Helsinki Music Institute (now the Sibelius Academy) where he studied from 1885 to 1889. One of his teachers was its founder, Martin Wegelius, who did much to support the development of education in Finland. It was he who gave the self-taught Sibelius his first formal lessons in composition.[22] Another important influence was his teacher Ferruccio Busoni, a pianist-composer with whom he enjoyed a lifelong friendship.[23] His close circle of friends included the pianist and writer Adolf Paul and the conductor-to-be Armas Järnefelt, (who introduced him to his influential family including his sister Aino who would become Sibelius's wife).[11] The most remarkable of his works during this period was the Violin Sonata in F, rather reminiscent of Grieg.[24]

Sibelius continued his studies in Berlin (from 1889 to 1890) with Albert Becker, and in Vienna (from 1890 to 1891) with Robert Fuchs and Hungarian-Jewish Karl Goldmark. In Berlin, he had the opportunity to widen his musical experience by going to a variety of concerts and operas, including the premiere of Richard Strauss's Don Juan. He also heard the Finnish composer Robert Kajanus conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in a program that included his symphonic poem Aino, a patriotic piece that may have triggered Sibelius's later interest in using the epic poem Kalevala as a basis for his own compositions.[23][25] While in Vienna, he became particularly interested in the music of Anton Bruckner whom, for a time, he regarded as "the greatest living composer", although he continued to show interest in the established works of Beethoven and Wagner. He enjoyed his year in Vienna, frequently partying and gambling with his new friends. It was also in Vienna that he turned to orchestral composition, working on an Overture in E major and a Scène de Ballet. While embarking on Kullervo, an orchestral work inspired by the Kalevala, he fell ill but was restored to good health after gallstone- excision surgery.[26] Shortly after returning to Helsinki, Sibelius thoroughly enjoyed conducting his Overture and the Scène de Ballet at a popular concert.[27] He was also able to continue working on Kullervo, now that he was increasingly developing an interest in all things Finnish. Premiered in Helsinki on 28 April 1892, the work was an enormous success.[11]

It was around this time that Sibelius finally abandoned his cherished aspirations as a violinist:

In addition to the long periods he spent studying in Vienna and Berlin (1889–91), in 1900 he travelled to Italy where he spent a year with his family. He composed, conducted and socialized actively in the Scandinavian countries, the UK, France and Germany and later travelled to the United States.[29]

Marriage and rise to fame

While Sibelius was studying music in Helsinki in the autumn of 1888, Armas Järnefelt, a friend from the Music Institute, invited him to the family home. There he met and immediately fell in love with Aino, the 17-year-old daughter of General Alexander Järnefelt, the governor of Vaasa, and Elisabeth Clodt von Jürgensburg, a Baltic aristocrat.[19] The wedding was held on 10 June 1892 at Maxmo. They spent their honeymoon in Karelia, the home of the Kalevala. It served as an inspiration for Sibelius's tone poem En saga, the Lemminkäinen legends and the Karelia Suite.[11] Their home, Ainola, was completed on Lake Tuusula, Järvenpää, in 1903. Over their years in Ainola, they had six daughters: Eva, Ruth, Kirsti (who died very young from typhoid),[30] Katarina, Margareta and Heidi.[31] Eva married an industrial heir, Arvi Paloheimo, and later became the CEO of the Paloheimo Corporation. Ruth Snellman was a prominent actress, Katarina Ilves married a banker and Heidi Blomstedt was a designer, wife of architect Aulis Blomstedt. Margareta married conductor Jussi Jalas, Aulis Blomstedt's brother.[32]

In 1892, the Kullervo inaugurated Sibelius's focus on orchestral music. It was described by the composer Aksel Törnudd as "a volcanic eruption" while Juho Ranta who sang in the choir stated, "It was Finnish music."[33] At the end of that year the composer's grandmother, Katarina Borg died. Sibelius went to her funeral, visiting his Hämeenlinna home one last time before the house was sold. On 16 February 1893, the first (extended) version of En saga was presented in Helsinki although it was not too well received, the critics suggesting that superfluous sections should be eliminated (as they were in Sibelius's 1902 version). Even less successful were three more performances of Kullervo in March, which one critic found was incomprehensible and lacking in vitality. Following the birth of Sibelius's first child Eva, in April the premiere of his choral work Väinämöinen's Boat Ride was a considerable success, receiving the support of the press.[34]

On 13 November 1893, the full version of Karelia was premiered at a student association gala at the Seurahuone in Viipuri with the collaboration of the artist Axel Gallénand the sculptor Emil Wikström who had been brought in to design the stage sets. While the first performance was difficult to appreciate over the background noise of the talkative audience, a second performance on 18 November was more successful. Furthermore, on the 19th and 23rd Sibelius presented an extended suite of the work in Helsinki, conducting the orchestra of the Philharmonic Society.[35] Sibelius's music was increasingly presented in Helsinki's concert halls. In the 1894–95 season, works such as En saga, Karelia and Vårsång (composed in 1894) were included in at least 16 concerts in the capital, not to mention those in Turku.[36] When performed in a revised version on 17 April 1895, the composer Oskar Merikanto welcomed Vårsång (Spring Song) as "the fairest flower among Sibelius's orchestral pieces".[37]

For a considerable period, Sibelius worked on an opera, Veneen luominen (The Building of the Boat), again based on the Kalevala. To some extent, he had come under the influence of Wagner, but subsequently turned to Liszt's tone poems as a source of compositional inspiration. Adapted from material for the opera, which he never completed, his Lemminkäinen Suiteconsisted of four legends in the form of tone poems.[11] They were premiered in Helsinki on 13 April 1896 to a full house. In contrast to Merikanto's enthusiasm for the Finnish quality of the work, the critic Karl Flodin found the cor anglais solo in The Swan of Tuonela "stupendously long and boring",[38][34] although he considered the first legend, Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island, as representing the peak of Sibelius's achievement to date.[39]

To pay his way, from 1892 Sibelius had taken on teaching assignments at the Music Institute and at Kajanus's conducting school but this left him insufficient time for composing.[40] The situation improved considerably when in 1898 he was awarded a substantial annual grant, initially for ten years and later extended for life. He was able to complete the music for Adolf Paul's play King Christian II. Performed on 24 February 1898, its catchy tunes appealed to the public. The scores of four popular pieces from the play were published in Germany and sold well in Finland. When the orchestral suite was successfully performed in Helsinki in November 1898, Sibelius commented: "The music sounded excellent and the tempi seem to be right. I think this is the first time that I have managed to make something complete." The work was also performed in Stockholm and Leipzig.[41]

In January 1899, Sibelius embarked on his First Symphony at a time when his patriotic feelings were being enhanced by the Russian emperor Nicholas II's attempt to restrict the powers of the Grand Duchy of Finland.[42] The symphony was well received by all when it was premiered in Helsinki on 26 April 1899. But the program also premiered the even more compelling, blatantly patriotic Song of the Athenians for boys' and men's choirs. The song immediately brought Sibelius the status of a national hero.[41][42] Another patriotic work followed on 4 November in the form of eight tableaux depicting episodes from Finnish history known as the Press Celebration Music. It had been written in support of the staff of the Päivälehti newspaper, which had been suspended for a period after editorially criticizing Russian rule.[43] The last tableau, Finland Awakens, was particularly popular; after minor revisions, it became the well-known Finlandia.[44]

In February 1900, Sibelius and his wife were deeply saddened by the death of their youngest daughter. Nevertheless, in the spring Sibelius went on an international tour with Kajanus and his orchestra, presenting his recent works (including a revised version of his First Symphony) in thirteen cities including Stockholm, Copenhagen, Hamburg, Berlin and Paris. The critics were highly favorable, bringing the composer international recognition with their enthusiastic reports in the Berliner Börsen-Courier, the Berliner Fremdenblatt and the Berliner Lokal Anzeiger.[45]

During a trip with his family to Rapallo, Italy in 1901, Sibelius began to write his Second Symphony, partly inspired by the fate of Don Juan in Mozart's Don Giovanni. It was completed in early 1902 with its premiere in Helsinki on 8 March. The work was received with tremendous enthusiasm by the Finns. Merikanto felt it exceeded "even the boldest expectations," while Evert Katila qualified it as "an absolute masterpiece".[45] Flodin, too, wrote of a symphonic composition "the likes of which we have never had occasion to listen to before".[46]

Sibelius spent the summer in Tvärminne near Hanko, where he worked on the song Var det en dröm (Was it a Dream) as well as on a new version of En saga. When it was performed in Berlin with the Berlin Philharmonic in November 1902, it served to firmly establish the composer's reputation in Germany, leading shortly afterwards to the publication of his First Symphony.[45]

In 1903, Sibelius spent much of his time in Helsinki where he indulged excessively in wining and dining, running up considerable bills in the restaurants. But he continued to compose, one of his major successes being Valse triste, one of six pieces of incidental music he composed for his brother-in-law Arvid Järnefelt's play Kuolema (Death). Short of money, he sold the piece at a low price but it quickly gained considerable popularity not only in Finland but internationally. During his long stays in Helsinki, Sibelius's wife Aino frequently wrote to him, imploring him to return home but to no avail. Even after their fourth daughter, Katarina, was born, he continued to work away from home. Early in 1904, he finished his Violin Concerto but its first public performance on 8 February was not a success. It led to a revised, condensed version that was performed in Berlin the following year.[47]

Move to Ainola

In November 1903, Sibelius began to build his new home Ainola (Aino's Place) near Lake Tuusula some 45 km (30 miles) north of Helsinki. To cover the construction costs, he gave concerts in Helsinki, Turku and Vaasa in early 1904 as well as in Tallinn, Estonia, and in Latvia during the summer. The family were finally able to move into the new property on 24 September 1904, making friends with the local artistic community, including the painters Eero Järnefelt and Pekka Halonen and the novelist Juhani Aho.[47]

In January 1905, Sibelius returned to Berlin where he conducted his Second Symphony. While the concert itself was successful, it received mixed reviews, some very positive while those in the Allgemeine Zeitung and the Berliner Tageblatt were less enthusiastic. Back in Finland, he rewrote the increasingly popular Pelléas and Mélisande as an orchestral suite. In November, visiting Britain for the first time, he went to Liverpool where he met Henry Wood. On 2 December, he conducted the First Symphony and Finlandia, writing to Aino that the concert had been a great success and widely acclaimed.[48]

In 1906, after a short, rather uneventful stay in Paris at the beginning of the year, Sibelius spent several months composing in Ainola, his major work of the period being Pohjola's Daughter, yet another piece based on the Kalevala. Later in the year he composed incidental music for Belshazzar's Feast, also adapting it as an orchestral suite. He ended the year conducting a series of concerts, the most successful being the first public performance of Pohjola's Daughter at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg.[48]

Ups and downs

From the beginning of 1907, Sibelius again indulged in excessive wining and dining in Helsinki, spending exorbitant amounts on champagne and lobster. His lifestyle had a disastrous effect on the health of Aino who was driven to retire to a sanatorium, suffering from exhaustion. While she was away, Sibelius resolved to give up drinking, concentrating instead on composing his Third Symphony. He completed the work for a performance in Helsinki on 25 September.[49] Although its more classical approach surprised the audience, Flodin commented that it was "internally new and revolutionary".[48]

Shortly afterwards Sibelius met Gustav Mahler who was in Helsinki. The two agreed that with each new symphony, they lost those who had been attracted to their earlier works. This was demonstrated above all in St Petersburg where the Third Symphony was performed in November 1907 to dismissive reviews. Its reception in Moscow was rather more positive.[48]

In 1907, Sibelius underwent a serious operation for suspected throat cancer. Early in 1908, Sibelius had to spend a spell in hospital. His smoking and drinking had now become life-threatening. Although he cancelled concerts in Rome, Warsaw and Berlin, he maintained an engagement in London but there too his Third Symphony failed to attract the critics. In May 1908, Sibelius's health deteriorated further. He travelled with his wife to Berlin to have a tumour removed from his throat. After the operation, he vowed to give up smoking and drinking once and for all.[48] The impact of this brush with death has been said to have inspired works that he composed in the following years, including Luonnotar and the Fourth Symphony.[50]

More pleasant times

In 1909, the successful throat operation resulted in renewed happiness between Sibelius and Aino in the family home. In Britain too, his condition was well received as he conducted En saga, Finlandia, Valse Triste and Spring Song to enthusiastic audiences. A meeting with Claude Debussy produced further support. After another uneventful trip to Paris, he went to Berlin where he was relieved to learn that his throat operation had been entirely successful.[51]

Sibelius started work on his Fourth Symphony in early 1910 but his dwindling funds also required him to write a number of smaller pieces and songs. In October, he conducted concerts in Kristiania (now Oslo) where The Dryad and In Memoriam were first performed. His Valse triste and Second Symphony were particularly well received. He then travelled to Berlin to continue work on his Fourth Symphony, writing the finale after returning to Järvenpää.[51]

Sibelius conducted his first concerts in Sweden in early 1911 when even his Third Symphony was welcomed by the critics. He completed the Fourth Symphony in April but, as he expected, with its introspective style it was not very warmly received when first performed in Helsinki with mixed reviews. Apart from a trip to Paris where he enjoyed a performance of Richard Strauss's Salome, the rest of the year was fairly uneventful. In 1912, he completed his short orchestral work Scènes historiques II. It was first performed in March together with the Fourth Symphony. The concert was repeated twice to enthusiastic audiences and critics including Robert Kajanus. The Fourth Symphony was also well received in Birmingham in September. In March 1913, it was performed in New York but a large section of the audience left the hall between the movements while in October, after a concert conducted by Carl Muck, the Boston American labelled it "a sad failure".[51]

Sibelius's first significant composition of 1913 was the tone poem The Bard, which he conducted in March to a respectful audience in Helsinki. He went on to compose Luonnotar (Daughter of Nature) for soprano and orchestra. With a text from the Kalevala, it was first performed in Finnish in September 1913 by Aino Ackté (to whom it had been dedicated) at the music festival in Gloucester, England.[51][52] In early 1914, Sibelius spent a month in Berlin where he was particularly drawn to Arnold Schönberg. Back in Finland, he began work on The Oceanides, which the American millionaire Carl Stoeckel had commissioned for the Norfolk Music Festival. After first composing the work in D flat major, Sibelius undertook substantive revisions, presenting a D major version in Norfolk, which was well received, as were Finlandia and the Valse triste. Henry Krehbiel considered The Oceanides one of the most beautiful pieces of sea music ever composed, while The New York Times commented that Sibelius's music was the most notable contribution to the music festival. While in America, Sibelius received an honorary doctorate from Yale University and, almost simultaneously, one from the University of Helsinki where he was represented by Aino.[51]

First World War years

While travelling back from the United States, Sibelius heard about the events in Sarajevo that led to the beginning of the First World War. Although he was far away from the fighting, his royalties from abroad were interrupted. To make ends meet, he was forced to compose lots of smaller works for publication in Finland. In March 1915, he was able to travel to Gothenburg in Sweden where his The Oceanides was really appreciated. While working on his Fifth Symphony in April, he saw 16 swans flying by, inspiring him to write the finale. "One of the great experiences of my life!" he commented. Although there was little progress on the symphony during the summer, he was able to complete it by his 50th birthday on 8 December.[53]

On the evening of his birthday, Sibelius conducted the premiere of the Fifth Symphony in the hall of the Helsinki Stock Exchange. Despite high praise from Kajanus, the composer was not satisfied with his work and soon began to revise it. Around this time, Sibelius was running ever deeper into debt. The grand piano he had received as a present was about to be confiscated by the bailiffs when the singer Ida Ekman paid off a large proportion of his debt after a successful fund-raising campaign.[53]

A year later, on 8 December 1916, Sibelius presented the revised version of his Fifth Symphony in Turku, combining the first two movements and simplifying the finale. When it was performed a week later in Helsinki, Katila was very favourable but Wasenius frowned on the changes, leading the composer to rewrite it once again.[53]

From the beginning of 1917, Sibelius started drinking again, triggering arguments with Aino. Their relationship improved with the excitement resulting from the start of the Russian Revolution. By the end of the year, Sibelius had composed his Jäger March. The piece proved particularly popular after the Finnish parliament accepted the Senate's declaration of independence from Russia in December 1917. The Jäger March, first played on 19 January 1918, delighted the Helsinki elite for a short time until the launch of the Finnish Civil War in 27 January.[53] Sibelius naturally supported the Whites, but as a tolstoyan, Aino Sibelius had some sympathies for the Redstoo.[54]

In February, the house Ainola was searched twice by the local Red Guard looking for weapons. During the first weeks of the war, some of his acquaintances were killed in the violence, and his brother, the psychiatrist Christian Sibelius, was arrested as he refused to reserve beds for the Red soldiers who had suffered shell shock at the front. Sibelius' friends in Helsinki were now worried about his safety. The composer Robert Kajanus had negotiations with the Red Guard commander-in-chief Eero Haapalainen, who guaranteed Sibelius a safe journey from Ainola to the capital. In 20 February, a group of Red Guard fighters escorted the family to Helsinki. Finally, in 12–13 April, the German troops occupied the city and the Red period was over. A week later, the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra gave a homage concert for the German commander Rüdiger von der Goltz, Sibelius finished off the event by conducting the Jäger March.[54]

Revived fortunes

In early 1919, Sibelius enthusiastically decided to change his image, removing his thinning hair. In June, together with Aino, he visited Copenhagen on his first trip outside Finland since 1915, successfully presenting his Second Symphony. In November he conducted the final version of his Fifth Symphony, receiving repeated ovations from the audience. By the end of the year, he was already working on the Sixth.[53]

In 1920, despite a growing tremor in his hands, Sibelius composed the Hymn of the Earth to a text by the poet Eino Leino for the Suomen Laulu Choir and orchestrated his Valse lyrique, helped along by drinking wine. On his birthday in December 1920, Sibelius received a donation of 63,000 marks, a substantial sum the tenor Wäinö Sola had raised from Finnish businesses. Although he used some of the money to reduce his debts, he also spent a week celebrating to excess in Helsinki.[55]

Sibelius enjoyed a highly successful trip to England in early 1921—conducting several concerts around the country, including the Fourth and Fifth symphonies, The Oceanides, the ever-popular Finlandia, and Valse triste. Immediately afterwards, he conducted the Second Symphony and Valse triste in Norway. He was beginning to suffer from exhaustion, but the critics remained positive. On his return to Finland in April, he presented Lemminkäinen's Return and the Fifth Symphony at the Nordic Music Days.[55]

Early in 1922, after suffering from headaches Sibelius decided to acquire spectacles although he never wore them for photographs. In July, he was saddened by the death of his brother Christian. In August, he joined the Finnish Freemasons and composed ritual music for them. In February 1923, he premiered his Sixth Symphony. Evert Katila highly praised it as "pure idyll." Before the year ended he had also conducted concerts in Stockholm and Rome, the first to considerable acclaim, the second to mixed reviews. He then proceeded to Gothenburg where he enjoyed an ecstatic reception despite arriving at the concert hall suffering from over-indulgence in food and drink. Despite continuing to drink, to Aino's dismay, Sibelius managed to complete his Seventh Symphony in early 1924. In March, under the title of Fantasia sinfonica it received its first public performance in Stockholm where it was a success. It was even more highly appreciated at a series of concerts in Copenhagen in late September. Sibelius was honoured with the Knight Commander's Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog.[55]

He spent most of the rest of the year resting as his recent spate of activity was straining his heart and nerves. Composing a few small pieces, he relied increasingly on alcohol. In May 1925, his Danish publisher Wilhelm Hansen and the Royal Danish Theatre invited him to compose incidental music for a production of Shakespeare's The Tempest. He completed the work well in advance of its premiere in March 1926.[55] It was well received in Copenhagen although Sibelius was not there himself.[56]

Last major contributions

The year 1926 saw a sharp and lasting decline in Sibelius's output: after his Seventh Symphony, he produced only a few major works during the rest of his life. Arguably the two most significant of these were the incidental music for The Tempest and the tone poem Tapiola.[57] For most of the last thirty years of his life, Sibelius even avoided talking publicly about his music.[58]

There is substantial evidence that Sibelius worked on an eighth symphony. He promised the premiere of this symphony to Serge Koussevitzky in 1931 and 1932, and a London performance in 1933 under Basil Cameron was even advertised to the public. The only concrete evidence of the symphony's existence on paper is a 1933 bill for a fair copy of the first movement and short draft fragments first published and played in 2011.[59][60][61][62] Sibelius had always been quite self-critical; he remarked to his close friends, "If I cannot write a better symphony than my Seventh, then it shall be my last." Since no manuscript survives, sources consider it likely that Sibelius destroyed most traces of the score, probably in 1945, during which year he certainly consigned a great many papers to the flames.[63] His wife Aino recalled,

On 1 January 1939, Sibelius participated in an international radio broadcast that included him conducting his Andante Festivo. The performance was preserved on transcription discs and later issued on CD. This is probably the only surviving example of Sibelius interpreting his own music.[65]

Final years and death

From 1903 and for many years thereafter Sibelius had lived in the countryside. From 1939 he and Aino again had a home in Helsinki but they moved back to Ainola in 1941, only occasionally visiting the city. After the war he returned to Helsinki only a couple of times. The so-called "the Silence of Järvenpää" became something of a myth, as in addition to countless official visitors and colleagues, his grandchildren and great grandchildren also spent their holidays in Ainola.[66]

Sibelius avoided public statements about other composers, but Erik W. Tawaststjerna and Sibelius's secretary Santeri Levas[67]have documented his private conversations in which he admired Richard Strauss and considered Béla Bartók and Dmitri Shostakovich the most talented composers of the younger generation.[68] In the 1950s he promoted the young Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara.[69]

His 90th birthday, in 1955, was widely celebrated and both the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra under Sir Thomas Beecham gave special performances of his music.[70][71]

Tawaststjerna also relates an anecdote in connection with Sibelius's death:[72]

Two days later in Ainola, on the evening of 20 September 1957, Sibelius died of a brain haemorrhage at age 91. At the time of his death, his Fifth Symphony, conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent, was being radio broadcast from Helsinki. At the same time, the United Nations General Assembly was in session and the then General Assembly President Sir Leslie Munro of New Zealand ordered a moment of silence, saying, "Sibelius belonged to the whole world. With his music, he enriched the life of the entire human race".[73] Another well-known Finnish composer, Heino Kaski, died the same day but his death was overshadowed by that of Sibelius. Sibelius was honoured with state funeral and is buried in the garden at Ainola.[74] Aino Sibelius lived there for the next 12 years until she died on 8 June 1969 aged 97; she is buried alongside her husband.[75]

Music

(See also: List of compositions by Jean Sibelius)

Sibelius is widely known for his symphonies and his tone poems, especially Finlandia and the Karelia suite. His reputation in Finland grew in the 1890s with the choral symphony Kullervo, which like many subsequent pieces drew on the epic poem Kalevala. His First Symphony was first performed to an enthusiastic audience in 1899 at a time when Finnish nationalism was evolving. In addition to six more symphonies, he gained popularity at home and abroad with incidental music and more tone poems, especially En saga, The Swan of Tuonela and Valse triste.[76] Sibelius also composed a series of works for violin and orchestra including a Violin Concerto, the opera Jungfrun i tornet, many shorter orchestral pieces, chamber music, works for piano and violin, choral works and numerous songs.[77]

In the mid-1920s, after his Sixth and Seventh Symphonies, he composed the symphonic poem Tapiola and incidental music for The Tempest. Thereafter, although he lived until 1957, he did not publish any further works of note. For several years, he worked on an Eighth Symphony, which he later burned.[78]

As for his musical style, hints of Tchaikovsky's music are particularly evident in early works such as his First Symphony and his Violin Concerto.[79] For a period, he was nevertheless overwhelmed by Wagner, particularly while composing his opera. More lasting influences included Ferruccio Busoni and Anton Bruckner. But for his tone poems, he was above all inspired by Liszt.[34][80] The similarities to Bruckner can be seen in the brass contributions to his orchestral works and the generally slow tempo of his music.[81][82]

Sibelius progressively stripped away formal markers of sonata form in his work and, instead of contrasting multiple themes, focused on the idea of continuously evolving cells and fragments culminating in a grand statement. His later works are remarkable for their sense of unbroken development, progressing by means of thematic permutations and derivations. The completeness and organic feel of this synthesis has prompted some to suggest that Sibelius began his works with a finished statement and worked backwards, although analyses showing these predominantly three- and four-note cells and melodic fragments as they are developed and expanded into the larger "themes" effectively prove the opposite.[83]

This self-contained structure stood in stark contrast to the symphonic style of Gustav Mahler, Sibelius's primary rival in symphonic composition.[57] While thematic variation played a major role in the works of both composers, Mahler's style made use of disjunct, abruptly changing and contrasting themes, while Sibelius sought to slowly transform thematic elements. In November 1907 Mahler undertook a conducting tour of Finland, and the two composers were able to take a lengthy walk together, leading Sibelius to comment:

Symphonies

Sibelius started work on his Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39, in 1898 and completed it in early 1899, when he was 33. The work was first performed on 26 April 1899 by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by the composer, in an original, well received version that has not survived. After the premiere, Sibelius made some revisions, resulting in the version performed today. The revision was completed in the spring and summer of 1900, and was first performed in Berlin by the Helsinki Philharmonic, conducted by Robert Kajanus on 18 July 1900.[85] The symphony begins with a highly original, rather forlorn clarinet solo backed by subdued timpani.[86]

His Second Symphony, the most popular and most frequently recorded of his symphonies, was first performed by the Helsinki Philharmonic Society on 8 March 1902, with the composer conducting. The opening chords with their rising progression provide a motif for the whole work. The heroic theme of the finale with the three-tone motif is interpreted by the trumpets rather than the original woodwinds. During a period of Russian oppression, it consolidated Sibelius's reputation as a national hero. After the first performance, Sibelius made some changes, leading to a revised version first performed by Armas Järnefelt on 10 November 1903 in Stockholm.[87]

The Third Symphony is a good-natured, triumphal, and deceptively simple-sounding piece. The symphony's first performance was given by the Helsinki Philharmonic Society, conducted by the composer, on 25 September 1907. There are themes from Finnish folk music in the work's early chords. Composed just after his move to Ainola, it contrasts sharply with the first two symphonies, with its clear mode of expression developing into the marching tones of the finale.[76][88] His Fourth Symphony was premiered in Helsinki on 3 April 1911 by the Philharmonia Society, with Sibelius conducting. It was written while Sibelius was undergoing a series of operations to remove a tumour from his throat. Its grimness can perhaps be explained as a reaction from his (temporary) decision to give up drinking. The opening bars, with cellos, basses and bassoons, convey a new approach to timing. It then develops into melancholic sketches based on the composer's setting of Poe's The Raven. The waning finale is perhaps a premonition of the silence Sibelius would experience twenty years later. In contrast to the usual assertive finales of the times, the work ends simply with a "leaden thud".[76]

Symphony No. 5 was premiered in Helsinki to great acclaim by Sibelius himself on 8 December 1915, his 50th birthday. The version most commonly performed today is the final revision, consisting of three movements, presented in 1919. The Fifth is Sibelius's only symphony in a major key throughout. From its soft opening played by the horns, the work develops into rotational repetitions of its various themes with considerable transformations, building up to the trumpeted swan hymn in the final movement.[76][89] While the Fifth had already started to veer away from the sonata form, the Sixth, conducted by the composer at its premiere in February 1923, is even further removed from the traditional norms. Tawaststjerna comments that "the [finale's] structure follows no familiar pattern".[90] Composed in the Dorian mode, it draws on some of the themes developed while Sibelius was working on the Fifth as well as from material intended for a lyrical violin concerto. Now taking a purified approach, Sibelius sought to offer "spring water" rather than cocktails making use of lighter flutes and strings rather than the heavy brass of the Fifth.[91]

Symphony No. 7 in C major was his last published symphony. Completed in 1924, it is notable for having only one movement. It has been described as "completely original in form, subtle in its handling of tempi, individual in its treatment of key and wholly organic in growth".[92] It has also been called "Sibelius's most remarkable compositional achievement".[93] Initially titled Fantasia sinfonica, it was first performed in Stockholm in March 1924, conducted by Sibelius. It was based on an adagio movement he had sketched almost ten years earlier. While the strings dominate, there is also a distinctive trombone theme.[94]

Tone poems

After the seven symphonies and the violin concerto, Sibelius's thirteen symphonic poems are his most important works for orchestra and, along with the tone poems of Richard Strauss, represent some of the most important contributions to the genre since Franz Liszt. As a group, the symphonic poems span the entirety of Sibelius's artistic career (the first was composed in 1892, while the last appeared in 1925), display the composer's fascination with nature and Finnish mythology (particularly the Kalevala), and provide a comprehensive portrait of his stylistic maturation over time.[95]

En saga (meaning a fairy tale) was first presented in February 1893 with Sibelius conducting. The single-movement tone poem was possibly inspired by the Icelandic mythological work Edda although Sibelius simply described it as "an expression of [his] state of mind". Beginning with a dreamy theme from the strings, it evolves into the tones of the woodwinds, then the horns and the violas, demonstrating Sibelius's ability to handle an orchestra.[96] The composer's first significant orchestral piece, it was revised in 1902 when Ferruccio Busoni invited Sibelius to conduct his work in Berlin. Its successful reception encouraged him to write to Aino: "I have been acknowledged as an accomplished 'artist'".[97]

The Wood Nymph, a single-movement tone poem for orchestra, was written in 1894. Premiered in April 1895 in Helsinki with Sibelius conducting, it is inspired by the Swedish poet Viktor Rydberg's work of the same name. Organizationally, it consists of four informal sections, each corresponding to one of the poem's four stanzas and evoking the mood of a particular episode: first, heroic vigour; second, frenetic activity; third, sensual love; and fourth, inconsolable grief. Despite the music's beauty, many critics have faulted Sibelius for his "over-reliance" on the source material's narrative structure.[98][99]

The Lemminkäinen Suite was composed in the early 1890s. Originally conceived as a mythological opera, Veneen luominen (The Building of the Boat), on a scale matching those by Richard Wagner, Sibelius later changed his musical goals and the work became an orchestral piece in four movements. The suite is based on the character Lemminkäinen from the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala. It can also be considered a collection of symphonic poems. The second/third section, The Swan of Tuonela, is often heard separately.[100]

Finlandia, probably the best known of all Sibelius's works, is a highly patriotic piece first performed in November 1899 as one of the tableaux for the Finnish Press Celebrations. It had its public premiere in revised form in July 1900.[44] The current title only emerged later, first for the piano version, then in 1901 when Kajanus conducted the orchestral version under the name Finlandia. Although Sibelius insisted it was primarily an orchestral piece, it became a world favourite for choirs too, especially for the hymn episode. Finally the composer consented and in 1937 and 1940 agreed to words for the hymn, first for the Free Masons and later for more general use.[101]

The Oceanides is a single-movement tone poem for orchestra written in 1913–14. The piece, which refers to the nymphs in Greek mythology who inhabited the Mediterranean Sea, premiered on 4 June 1914 at the Norfolk Music Festival in Connecticut with Sibelius himself conducting. The work (in D major), praised upon its premiere as "the finest evocation of the sea ever produced in music",[102] consists of two subjects Sibelius gradually develops in three informal stages: first, a placid ocean; second, a gathering storm; and third, a thunderous wave-crash climax. As the tempest subsides, a final chord sounds, symbolizing the mighty power and limitless expanse of the sea.[103]

Tapiola, Sibelius's last major orchestral work, was commissioned by Walter Damrosch for the New York Philharmonic Society where it was premiered on 26 December 1926. It is inspired by Tapio, a forest spirit from the Kalevala. To quote the American critic Alex Ross, it "turned out to be Sibelius's most severe and concentrated musical statement."[76] Even more emphatically, the composer and biographer Cecil Gray asserts: "Even if Sibelius had written nothing else, this one work would entitle him to a place among the greatest masters of all time."[104]

Other important works

The Karelia Music, one of the composer's earlier works, written for the Vyborg Students' Association, was first performed on 13 November 1893 to a noisy audience. The "Suite" emerged from a concert on 23 November consisting of the overture and the three movements, which were published as Op. 11, the Karelia Suite. It remains one of Sibelius's most popular pieces.[105]

Valse triste is a short orchestral work that was originally part of the incidental music Sibelius composed for his brother-in-law Arvid Järnefelt's 1903 play Kuolema. It is now far better known as a separate concert piece. Sibelius wrote six pieces for the 2 December 1903 production of Kuolema (meaning death). The waltz accompanied a sequence in which a woman rises from her deathbed to dance with ghosts. In 1904, Sibelius revised the piece for a performance in Helsinki on 25 April where it was presented as Valse triste. An instant success, it took on a life of its own, and remains one of Sibelius's signature pieces.[47][106]

The Violin Concerto in D minor was first performed on 8 February 1904 with Victor Nováček as soloist. As Sibelius had barely completed the piece in time for the premiere, Nováček had insufficient time to prepare with the result that the performance was a disaster. After substantial revisions, a new version was premiered on 19 October 1905 with Richard Strauss conducting the Berlin Court Orchestra. With Karel Halíř, the orchestra's leader, as soloist it was a tremendous success.[107] The piece has become increasingly popular and is now the most frequently recorded of all the violin concertos composed in the 20th century.[108]

Kullervo, one of Sibelius's early works, is sometimes referred to as a choral symphony but is better described as a suite of five symphonic movements resembling tone poems.[109] Based on the character Kullervo from the Kalevala, it was premiered on 28 April 1892 with Emmy Achté and Abraham Ojanperä as soloists and Sibelius conducting the chorus and orchestra of the recently founded Helsinki Orchestra Society. Although the work was only performed five times during the composer's lifetime, since the 1990s it has become increasingly popular both for live performances and recordings.[110]

Freemasonry

When Freemasonry was revived in Finland, having been forbidden under the Russian reign, Sibelius was one of the founding members of Suomi Lodge No. 1 in 1922 and later became the Grand Organist of the Grand Lodge of Finland. He composed the ritual music used in Finland (Op. 113) in 1927 and added two new pieces composed in 1946. The new revision of the ritual music of 1948 is one of his last works.[111]

Νature

Sibelius loved nature, and the Finnish landscape often served as material for his music. He once said of his Sixth Symphony, "[It] always reminds me of the scent of the first snow." The forests surrounding Ainola are often said to have inspired his composition of Tapiola. On the subject of Sibelius's ties to nature, his biographer, Tawaststjerna, wrote:

Reception

Sibelius exerted considerable influence on symphonic composers and musical life, at least in English-speaking and Nordic countries. The Finnish symphonist Leevi Madetoja was a pupil of Sibelius (for more on their relationship, see Madetoja and Sibelius). In Britain, Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax both dedicated their fifth symphonies to Sibelius. Furthermore, Tapiola is prominently echoed in both Bax's Sixth Symphony and Moeran's Symphony in G Minor.[113][114] The influence of Sibelius's compositional procedures is also strongly felt in the First Symphony of William Walton.[115] When these and several other major British symphonic essays were being written in and around the 1930s, Sibelius's music was very much in vogue, with conductors like Beecham and Barbirolli championing its cause both in the concert hall and on record. Walton's composer friend Constant Lambert even asserted that Sibelius was "the first great composer since Beethoven whose mind thinks naturally in terms of symphonic form".[116] Earlier, Granville Bantock had championed Sibelius (the esteem was mutual: Sibelius dedicated his Third Symphony to the English composer, and in 1946 he became the first President of the Bantock Society). More recently, Sibelius was also one of the composers championed by Robert Simpson. Malcolm Arnold acknowledged his influence, and Arthur Butterworth also saw Sibelius's music as a source of inspiration in his work.[117]

Eugene Ormandy and to a lesser extent, his predecessor with the Philadelphia Orchestra Leopold Stokowski, were instrumental in bringing Sibelius's music to American audiences by frequently programming his works; the former developed a friendly relationship with Sibelius throughout his life. Later in life, Sibelius was championed by the American critic Olin Downes, who wrote a biography of the composer.[118]

In 1938 Theodor Adorno wrote a critical essay, notoriously charging that "If Sibelius is good, this invalidates the standards of musical quality that have persisted from Bach to Schoenberg: the richness of inter-connectedness, articulation, unity in diversity, the 'multi-faceted' in 'the one'."[119] Adorno sent his essay to Virgil Thomson, then music critic of the New York Herald Tribune, who was also critical of Sibelius; Thomson, while agreeing with the essay's sentiment, declared to Adorno that "the tone of it [was] more apt to create antagonism toward [Adorno] than toward Sibelius".[64] Later, the composer, theorist and conductor René Leibowitz went so far as to describe Sibelius as "the worst composer in the world" in the title of a 1955 pamphlet.[120]

Perhaps one reason Sibelius has attracted both the praise and the ire of critics is that in each of his seven symphonies he approached the basic problems of form, tonality, and architecture in unique, individual ways. On the one hand, his symphonic (and tonal) creativity was novel, while others thought that music should be taking a different route.[121] Sibelius's response to criticism was dismissive: "Pay no attention to what critics say. No statue has ever been put up to a critic."[76]

In the latter decades of the twentieth century, Sibelius became seen more favourably: Milan Kundera said the composer's approach was that of "antimodern modernism," standing outside the perpetual progression of the status quo.[64] In 1990, the composer Thea Musgrave was commissioned by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra to write a piece in honour of the 125th anniversary of Sibelius's birth: Song of the Enchanter premiered on 14 February 1991.[122] In 1984, the American avant-garde composer Morton Feldman gave a lecture in Darmstadt, Germany, wherein he stated that "the people you think are radicals might really be conservatives – the people you think are conservatives might really be radical," whereupon he began to hum Sibelius's Fifth Symphony.[64]

Writing in 1996, the Pulitzer Prize-winning music critic Tim Page stated, "There are two things to be said straightaway about Sibelius. First, he is terribly uneven (much of his chamber music, a lot of his songs and most of his piano music might have been churned out by a second-rate salon composer from the 19th century on an off afternoon). Second, at his very best, he is often weird."[123] Pianist Leif Ove Andsnes offers a counterweight to Page's assessment of Sibelius's piano music. Acknowledging that this body of work is uneven in quality, Andsnes believes that the common critical dismissal is unwarranted. In performing selected piano works, Andsnes finds that audiences were "astonished that there could be a major composer out there with such beautiful, accessible music that people don't know."[124]

With 8 December 2015 being the 150th anniversary of Sibelius's birth, the Helsinki Music Centre has planned an illustrated and narrated "Sibelius Finland Experience Show" every day during the summer of 2015. The production is also planned to extend over 2016 and 2017.[125] On 8 December itself, the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by John Storgårds has planned a commemorative concert featuring En Saga, Luonnotar and the Seventh Symphony.[126]

Legacy

In 1972, Sibelius's surviving daughters sold Ainola to the State of Finland. The Ministry of Education and the Sibelius Society of Finland opened it as a museum in 1974. The Finnish 100 mark bill featured his image until 2002 when the euro was adopted.[4] Since 2011, Finland has celebrated a Flag Day on 8 December, the composer's birthday, also known as the "Day of Finnish Music".[5] The year 2015, the 150th anniversary of the composer's birth, featured a number of special concerts and events, especially in the city of Helsinki.[6]

The quinquennial International Jean Sibelius Violin Competition, instituted in 1965, the Sibelius Monument, unveiled in 1967 in Helsinki's Sibelius Park, the Sibelius Museum, opened in Turku in 1968, and the Sibelius Hall concert hall in Lahti, opened in 2000, were all named in his honour, as was the asteroid 1405 Sibelius.[127]

Sibelius kept a diary in 1909–1944, and his family allowed it to be published, unabridged, in 2005. The diary was edited by Fabian Dahlström and published in the Swedish language in 2005.[128] To celebrate the 150th anniversary of the composer, the entire diary was also published in the Finnish language in 2015.[129] Several volumes of Sibelius’ correspondence have also been edited and published in Swedish, Finnish and English.

See also:

ΠΑΡΑΠΟΜΠΕΣ - ΠΗΓΕΣ:

2. MUSIC-VIDEOS:

( Πηγή:Sergio Cánovas)

Jean Sibelius - Symphony No.1 in E minor,Opus 39

I - Andante ma non troppo - Allegro energico: 0:00

II - Andante ma non troppo lento: 11:16

III - Scherzo. Allegro - Lento - Tempo I: 20:39

IV - Finale quasi una fantasia. Andante - Allegro molto - Andante assai - Allegro molto - Andante: 25:51

BBC Philharmonic conducted by John Storgårds

II - Andante ma non troppo lento: 11:16

III - Scherzo. Allegro - Lento - Tempo I: 20:39

IV - Finale quasi una fantasia. Andante - Allegro molto - Andante assai - Allegro molto - Andante: 25:51

BBC Philharmonic conducted by John Storgårds

The first Symphony of Sibelius was written in 1898 and premiered in 1899, at the time that the Russian oppression began and the performance was done after only two months in which was published the Russian Manifesto in which the autonomy of Finland was drastically reduced. In the same program the "Atenarnes sång" was interpreted, which was very well received by the nationalists to whom he invited the fight. Equally it was the symphony, that although it was not a programmatic work, its music had a very nationalistic charisma.

The first movement begins with a melancholy melody on the clarinet on soft rolls of the timpani. Then enter the strings, presenting the first theme of the allegro in sonata form, a theme of lively character. The second theme appears in pianissimo with tremolos on the violins and syncopations on the harp. The exhibition ends with a crescendo in which he uses the bass horn. Follow the development section that leads to the classic repetition of the themes in the recapitulation. A long crescendo leads us to the coda.

The second movement is written in the tripartite form of lied. The theme is romantic, expressed warmly. The central part contains a section for bassons in counterpoint, which according to Sibelius has a strong Finnish flavor. This section contains a long development that leads to an angry allegro. It ends with the lyrical melody of the main theme that fades slowly.

The third movement is the scherzo. It begins rhythmically with a repetitive theme, underlined by the timpani. The central section corresponds to the trio, which has a calm character with solos of the horns and the flute. But soon the rhythmic first part returns, which closes the movement.

The last movement begins with the strings interpreting the clarinet theme, with which the work was opened. After a quiet section of tragic character, which ends with dramatic calls, the clarinets introduce a melodic noble theme, which is taken by the whole orchestra. But contrary to expectations, the tragic climate reappears with metal calls that seem to invite the fight, consolidating the work as stormy. The lyrical theme played warmly by the orchestra reappears, a theme that reminds us of Tchaikovsky. But as if it were a tribute to the Russian author, the work ends tragically with strong chords of the wind accompanied by percussion.

The first movement begins with a melancholy melody on the clarinet on soft rolls of the timpani. Then enter the strings, presenting the first theme of the allegro in sonata form, a theme of lively character. The second theme appears in pianissimo with tremolos on the violins and syncopations on the harp. The exhibition ends with a crescendo in which he uses the bass horn. Follow the development section that leads to the classic repetition of the themes in the recapitulation. A long crescendo leads us to the coda.

The second movement is written in the tripartite form of lied. The theme is romantic, expressed warmly. The central part contains a section for bassons in counterpoint, which according to Sibelius has a strong Finnish flavor. This section contains a long development that leads to an angry allegro. It ends with the lyrical melody of the main theme that fades slowly.

The third movement is the scherzo. It begins rhythmically with a repetitive theme, underlined by the timpani. The central section corresponds to the trio, which has a calm character with solos of the horns and the flute. But soon the rhythmic first part returns, which closes the movement.

The last movement begins with the strings interpreting the clarinet theme, with which the work was opened. After a quiet section of tragic character, which ends with dramatic calls, the clarinets introduce a melodic noble theme, which is taken by the whole orchestra. But contrary to expectations, the tragic climate reappears with metal calls that seem to invite the fight, consolidating the work as stormy. The lyrical theme played warmly by the orchestra reappears, a theme that reminds us of Tchaikovsky. But as if it were a tribute to the Russian author, the work ends tragically with strong chords of the wind accompanied by percussion.

Although there is no programmatic explanation we can see this work as formally patriotic, celebrating the bitter resistance of the Finnish people and trying to wake up to fight for their rights.

(Read more: Sibelius :Symphony No. 1)

(Πηγή:Classical Music goturhjem2)

Jean Sibelius - Symphony No. 2, in D major, Op. 43

1.Allegretto

2.Tempo andante ma rubato - Andante sostenuto

2.Tempo andante ma rubato - Andante sostenuto

3.Vivacissimo - Lento e suave

4.Finale. Allegro moderato - Poco largamente

Iceland Symphony Orchestra,Petri Sakari.

The genesis of the Second Symphony can be traced to Sibelius' trip to Italy in early 1901. The trip came about at the suggestion of his friend, the amateur musician Axel Carpelan, and it was there that he began contemplating several ambitious projects, including a four-movement tone poem based on the Don Juan story and a setting of Dante's Divina Commedia. While none of these plans ever came to fruition, some of the ideas sketched during this trip did find their way into the second movement of this symphony. Carpelan was also instrumental in raising money to allow Sibelius to relinquish his work at the Helsinki Conservatoire and devote himself to the composition of the Second Symphony. Despite his friend's help, Sibelius' return to Finland for the summer and autumn was not accompanied by any great burst of inspiration, and extensive revisions delayed the first performance, first to January 1902 and then to March 1903. But from then on, the symphony enjoyed unparalleled success in Finland and eventually led to the major breakthrough in Germany that was so craved by Scandinavian composers of this era (one which Nielsen, for instance, never achieved). The Second Symphony has retained an extraordinary popularity for its individualistic tonal language, dark wind coloring, muted string writing, simple folk-like themes, and distinctly "national" flavor that are all Sibelian to the core.

While the opening mood is pastoral, it leads to an air of instability, in which small, short gestures seem to arise at random and then trail off. Yet there is a subtle coherence to the work that counters its seemingly shapeless quality. All of the material of the first movement emerges from either the two repeated-note subjects heard in the strings and winds at the opening, or from a brooding idea first presented in the winds and brass.

Unlike the first movement, in which the gentleness of the introduction is recaptured at the conclusion, the second movement is full of turbulence and ends without consolation. Two competing subjects seem to engage in a battle: First, a dirge-like bassoon melody in D minor, marked "lugubrious," builds to a towering culmination in winds and brass; then an ethereal, ruminative theme is played by divided strings in the key of F sharp major. The energetic scherzo, with its machine-gun figures in the strings, is built from a fragment of greatest simplicity: a repeated B flat followed by a turn around that note.

Following the precedent of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, the Scherzo is linked directly to the finale through a grand rhetorical bridge passage. The symphony at last achieves a flowing D major melodic line that heroically shakes off the D minor preparation, in the best sense of the Romantic tradition. Also like Beethoven, Sibelius brings back the transitional material a second time so that the victory of the major key can be savored anew, after which he concludes the work with a hymn-like peroration. That said, the Second Symphony marks the end of Sibelius' early Romantic period that paid homage to his predecessors. In subsequent works, his interest rested more in pursing new formal methods based on fragmentation and recombination.

(Read more: Sibelius:Symphony No. 2)

While the opening mood is pastoral, it leads to an air of instability, in which small, short gestures seem to arise at random and then trail off. Yet there is a subtle coherence to the work that counters its seemingly shapeless quality. All of the material of the first movement emerges from either the two repeated-note subjects heard in the strings and winds at the opening, or from a brooding idea first presented in the winds and brass.

Unlike the first movement, in which the gentleness of the introduction is recaptured at the conclusion, the second movement is full of turbulence and ends without consolation. Two competing subjects seem to engage in a battle: First, a dirge-like bassoon melody in D minor, marked "lugubrious," builds to a towering culmination in winds and brass; then an ethereal, ruminative theme is played by divided strings in the key of F sharp major. The energetic scherzo, with its machine-gun figures in the strings, is built from a fragment of greatest simplicity: a repeated B flat followed by a turn around that note.

Following the precedent of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, the Scherzo is linked directly to the finale through a grand rhetorical bridge passage. The symphony at last achieves a flowing D major melodic line that heroically shakes off the D minor preparation, in the best sense of the Romantic tradition. Also like Beethoven, Sibelius brings back the transitional material a second time so that the victory of the major key can be savored anew, after which he concludes the work with a hymn-like peroration. That said, the Second Symphony marks the end of Sibelius' early Romantic period that paid homage to his predecessors. In subsequent works, his interest rested more in pursing new formal methods based on fragmentation and recombination.

(Read more: Sibelius:Symphony No. 2)

(Πηγή: Classical Music goturhjem2)

Jean Sibelius - Symphony No. 3, Op. 52

Op. 52 Symphony no. 3 in C major:

1. Allegro moderato, 00:02

2. Andantino con moto, quasi allegretto, 11:21

3. Moderato - Allegro ma non tanto. 22:12

The Danish National Symphony Orchestra. Leif Segerstam, conductor.

Completed in 1907; first performance in Helsinki, 25th September 1907 (Orchestra of Helsinki Philharmonic Society under Jean Sibelius).

Sibelius's third symphony has been regarded as more classical than his previous works. The scholar Gerald Abraham has argued that the first movement bears strong comparison with the first movements of Haydn's and Mozart's symphonies. Against this background, it seems all the more remarkable that the history of its composition has turned out to be quite complicated.

Influences from Finnish folk music are discernible in the very first chords of the symphony. There were also some programmatic notions behind it. In Paris in January 1906, after a period of lively celebrations, Sibelius played three themes to the painter Oscar Parviainen. These were: Funeral March, A Prayer to God and A Great Feast. The scholar Markku Hartikainen has shown that these themes were probably connected with Jalmari Finne's libretto for the oratorio Marjatta, which Sibelius did not manage to compose despite several attempts. However, the Prayer to God theme ended up as a hymn theme within the finale of the third symphony -- and it also appeared on the wall at Ainola, for the theme inspired Oscar Parviainen to produce a painting for Sibelius.

In 1906 Sibelius completed the orchestral poem Pohjola's Daughter. The sketches for the work contain material which ended up in the third symphony. Thus, it seems that the symphony, which in itself was heard as a non-programmatic work, received - as is often the case with Sibelius - its initial stimulus from various programmatic ideas; these lost their programmatic meaning during the process of composition as the material was reworked in purely musical terms.

Sibelius conducted the first public performance on 25th September 1907. The reviews were mixed: Karl Flodin praised the work, but the Helsingin Sanomat reviewer claimed that the direct impact of the work was weaker than that of the first symphony.

Sibelius's third symphony has been regarded as more classical than his previous works. The scholar Gerald Abraham has argued that the first movement bears strong comparison with the first movements of Haydn's and Mozart's symphonies. Against this background, it seems all the more remarkable that the history of its composition has turned out to be quite complicated.

Influences from Finnish folk music are discernible in the very first chords of the symphony. There were also some programmatic notions behind it. In Paris in January 1906, after a period of lively celebrations, Sibelius played three themes to the painter Oscar Parviainen. These were: Funeral March, A Prayer to God and A Great Feast. The scholar Markku Hartikainen has shown that these themes were probably connected with Jalmari Finne's libretto for the oratorio Marjatta, which Sibelius did not manage to compose despite several attempts. However, the Prayer to God theme ended up as a hymn theme within the finale of the third symphony -- and it also appeared on the wall at Ainola, for the theme inspired Oscar Parviainen to produce a painting for Sibelius.

In 1906 Sibelius completed the orchestral poem Pohjola's Daughter. The sketches for the work contain material which ended up in the third symphony. Thus, it seems that the symphony, which in itself was heard as a non-programmatic work, received - as is often the case with Sibelius - its initial stimulus from various programmatic ideas; these lost their programmatic meaning during the process of composition as the material was reworked in purely musical terms.

Sibelius conducted the first public performance on 25th September 1907. The reviews were mixed: Karl Flodin praised the work, but the Helsingin Sanomat reviewer claimed that the direct impact of the work was weaker than that of the first symphony.

Stylistically, Sibelius was now approaching notions of Neoclassical music in ways that his friend Ferruccio Busoni would write about a short time later. Sibelius's third symphony is more condensed than its predecessors. Now there are three movements instead of four, since the scherzo and the finale are combined more organically than in the second symphony.

Romanticism is replaced by functionalism, and the orchestration is lighter than before, with no tuba or harp. In his old age Sibelius was of the opinion that the third symphony need not be performed with an orchestra of more than fifty players.

From time to time the rhythm becomes as important as the melodic material. In this way Sibelius anticipated the rhythmic innovations of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring.

The symphony begins with a pithy main motif in the cellos and the basses. As no underpinning harmony is heard, the melody, apparently in C major, can also be regarded as a reminiscence of the Kalevala melody which Sibelius wrote down during his journey in 1892, when he set out to collect traditional poems and songs.

Romanticism is replaced by functionalism, and the orchestration is lighter than before, with no tuba or harp. In his old age Sibelius was of the opinion that the third symphony need not be performed with an orchestra of more than fifty players.

From time to time the rhythm becomes as important as the melodic material. In this way Sibelius anticipated the rhythmic innovations of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring.

The symphony begins with a pithy main motif in the cellos and the basses. As no underpinning harmony is heard, the melody, apparently in C major, can also be regarded as a reminiscence of the Kalevala melody which Sibelius wrote down during his journey in 1892, when he set out to collect traditional poems and songs.

(Read more: Sibelius:Symphony No.3)

(Πηγή: Rique Borges)

Jean Sibelius - Symphony No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 63

Jean Sibelius:4.a-moll Szimfónia Op.63

1.Tempo molto moderato, quasi adagio 00:00

2.Allegro molto vivace 11:12

3. Il tempo largo 16:07

4.Allegro 27:32

Helsinki Filharmonikus Zenekar. Vezényel:Leif Segerstam

Helsinki Filharmonikus Zenekar. Vezényel:Leif Segerstam

The fourth symphony was once considered to be the strangest of Sibelius's symphonies, but today it is regarded as one of the peaks of his output. It has a density of expression, a chamber music-like transparency and a mastery of counterpoint that make it one of the most impressive manifestations of modernity from the period when it was written.

Sibelius had thoughts of a change of style while he was in Berlin in 1909. These ideas were still in his mind when he joined the artist Eero Järnefelt for a trip to Koli, the emblematic "Finnish mountain" in Karelia, close to Joensuu. The landscape of Koli was for Järnefelt an endless source of inspiration, and Sibelius said that he was going to listen to the "sighing of the winds and the roar of the storms". Indeed, the composer regarded his visit to Koli as one of the greatest experiences of his life. "Plans. La Montagne," he wrote in his diary on 27th September 1909.

The following year Sibelius was again travelling in Karelia, in Vyborg and Imatra, now acting as a guide to his friend and sponsor Rosa Newmarch. Newmarch later recollected how Sibelius eagerly strained his ears to hear the pedal points in the roar of Imatra's famous rapids and in other natural sounds.

The trip also had other objectives. On his return Sibelius wanted to develop his skills in counterpoint, since, as he put it, "the harmony is largely dependent on the purely musical patterning, its polyphony." His observations contained many ideas on the need for harmonic continuity. Since the orchestra lacked the pedal of the piano, Sibelius wanted to compensate for this with even more skilful orchestration.

Yet one more natural phenomenon -- a storm in the south-eastern archipelago -- was needed to get the symphonic work started. In addition, in November 1910 he was preparing the symphony at the same time as he was working on music for Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven, which he had promised to Aino Ackté. The Raven was never finished, but its atmosphere and sketches had an effect on the fourth symphony.

The symphony was performed for the first time on 3rd April 1911, in Helsinki. Its tone was both modern and introspective, and it confused the audience so much that the applause was subdued. "Evasive glances, shakes of the head, embarrassed or secretly ironic smiles. Not many came to the dressing room to deliver their congratulations," Aino Sibelius recollected later. The critics, too, were at a loss. "Everything was so strange," was how Heikki Klemetti described the atmosphere. In the years that followed audiences in many parts of the world reacted the same way.

However, Sibelius remained happy with the symphony and after the first public performance he prepared it for publication. Nowadays, the fourth symphony has come to be recognised as one of the great masterpieces of the 20th century and one of Sibelius's most magnificent achievements. It was, after all, contemporary music of the utmost modernity, a work from which all traces of aesthetisation or artificiality had been eliminated.

A kind of motto for the work is the augmented fourth, or tritone, which creates tension in all the four movements of the symphony. The atmosphere of the work varies from joyfulness to austere expressionism. Every movement fades into silence. We are as far as we could be from the triumphant finales of the second and third symphonies.